History . Franny Taft

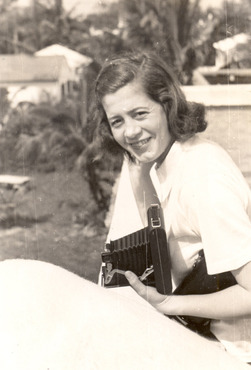

Frances P. Taft

1922-2017

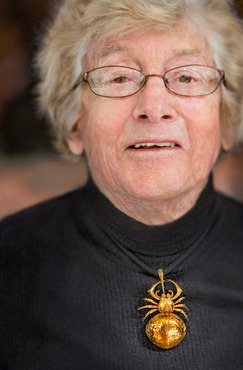

Professor Emerita Franny Taft influenced generations of artists by teaching at CIA for an astounding 62 years.

When Franny Taft ran out of room for art, when every bit of wall in her Pepper Pike home was covered in paintings and photographs, she didn’t take it as a sign to stop collecting and displaying. She took it as a sign to add on to the house.

That overwhelming love of art and a passion for teaching combined to make her one of the most influential and loved faculty members in the history of the Cleveland Institute of Art. As much as any faculty member, she helped integrate the liberal arts into the curriculum.

Frances P. (Franny) Taft taught at CIA for 62 years, joining the faculty of the then-Cleveland School of Art in 1950 and retiring in 2012. She taught longer than anyone else, long enough to see former students return as faculty members.

CIA President + CEO Grafton Nunes recalls that "when I became president of CIA, I met this extraordinary person whose intelligence, empathy, values and love for CIA just shone through everything she said and did. I realized she started teaching at CIA the year I was born. That was daunting. Then I realized that she taught my mother to be a radio operator in the WAVES during the second world war, and that was so personally meaningful to me. She was a mother to all of us at CIA, and we all love her."

Former CIA President David Deming was taught by Taft in the 1960s, became president and CEO of the institute in 1998 and retired in 2010 — two years before Taft took her leave. “Not only was she a teacher, a truly great teacher, she was a mentor,” Deming said in an archived interview.

A native of New Haven, Conn., Taft could easily have lived her life in those comfortable surroundings, but her intellectual curiosity, individuality and restless streak would not allow it.

She majored in biology and minored in art history at Vassar College with the idea of becoming a medical illustrator. She married Seth Taft, the grandson of President William Howard Taft, and, in 1943, joined the Navy’s first class of WAVES (Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service), where she taught codes and ciphers.

After World War II ended, she did cancer research and earned a master’s degree in art history at Yale.

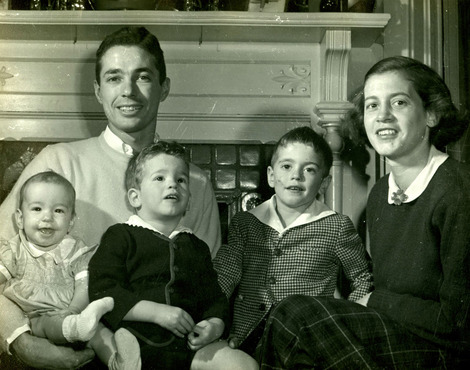

The young couple relocated to Cleveland in 1948. He joined the law firm then known as Jones Day Reavis & Pogue, and within two years she was teaching Western art history at the Cleveland Institute of Art.

In the 1960s, in order to become a five-year, degree-granting institution, the school needed to add liberal arts courses. Taft volunteered to teach pre-Colombian culture, a subject she knew nothing about, but which she tackled with typical vigor. “I had to teach myself,” she said. “I never had a course in it in my life. Everything was new.”

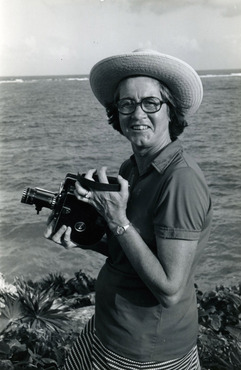

Unwilling to settle for merely reading about the subject, she traveled throughout Mexico and Central and South America, collecting items, visiting archaeological sites and interviewing scholars until she became expert.

She visited more than 30 countries for research and pleasure and documented each trip in journals she illustrated with sketches and watercolors, though she never claimed to have much artistic skill. For her 80th birthday, she visited the Galapagos Islands with her husband, their four children and their families.

She spread her curiosity to students as well as faculty. Retired design professor Richard Fiorelli, who joined CIA in the 1980s, recalled the lesson Taft used.

“She asked me to imagine a fireplug. We see them every day and pay little notice. Obviously you could sketch, draw or even paint one. Then she asked me to imagine what was not visible below the surface. She asked me to imagine the branch-like infrastructure not visible to the eye. Imagine the network that connects the buildings, streets, etc. Her point was simply and brilliantly made. Start with the seemingly simple examination of one thing and see where it leads you. Curiosity,” he said.

Gary Sampson, chair of CIA’s Liberal Arts Department, remembered her kindness in inviting him to her art-filled house for dinner when he was interviewing for a job at the institute.

“She definitely makes an impression. Her legacy is certain to resound through the halls of CIA. She is one of the people who helped make the school what it is,” he said.

She collected art throughout her career from colleagues and students, even commissioning pieces, and her home has been a gallery as much as a domicile, each work accompanied by a card with a title and the artist’s name.

A gregarious networker and formidable fundraiser, she sat on the boards of Western Reserve Academy, Laurel School, the Cleveland Museum of Art, the Cleveland Archaeological Society and Karamu House. Seth was active in Republican politics and served as Cuyahoga County commissioner in the 1970s. He also ran for mayor of Cleveland and governor. He died in 2013.

She was typically modest about her accomplishments, declaring herself neither an artist nor a scholar. When she was honored with the Cleveland Arts Prize in 1995, she said, “I don’t know what they’re doing. I haven’t done anything special. It’s probably for longevity, for hanging in there.”

If someone had made a film of her life, she might have been played by Katharine Hepburn: whip-smart, confident, outspoken and unwilling to set herself limitations or accept those imposed by others.

“I’m really a doer,” Taft said once with typical understatement. “I always participated. I always wanted to be in what the heck was going on. That’s probably why I ended up in the soup with too much to do.”

Contributions to the Frances P. Taft Scholarship may be made by sending a check to the Cleveland Institute of Art, 11610 Euclid Ave., Cleveland, OH 44106. Donations can be made online.