Blog . CinemaTalk, March-April 2019

Blog

03/01/19 | Posted by John Ewing | Posted in Cinematheque

By John Ewing, Cinematheque Director.

I recently was a guest on Cleveland Cinemas’ weekly podcast. After the recording session, I mentioned to the show’s two co-hosts, Dave Huffman and Aaron Spears, that I was going straight to the memorial service for Morrie Zryl at a nearby funeral home. When they both told me they didn’t know who Morrie was, I was stunned; Dave, the longtime marketing director for Cleveland Cinemas, and Aaron, veteran house manager at the Cedar Lee Theatre, are two very savvy movie guys. But then I thought about it. How could these relatively young men know about Morrie, who had lived and worked in Florida for the past 20 years, and who died there, suddenly and unexpectedly, on January 16 at age 69?

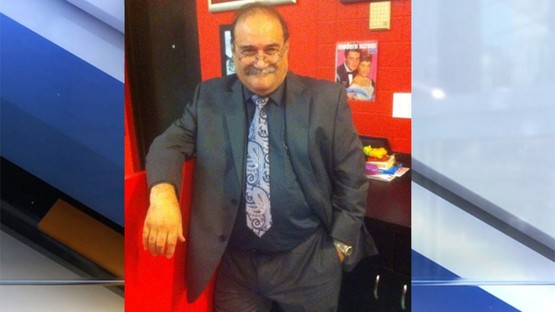

Morrie Zryl was one of the pillars of the local film scene during the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s. (Granted, the image of Morrie as any sort of “pillar” is a bit comical; he was short and stocky with glasses and a walrus mustache, and he moved and talked constantly.) A graduate of Cleveland Heights High School, Morrie entered the movie business as an usher at the Cedar Lee Theatre starting in 1966, while still a teenager. Later he became assistant manager—and, during the 1980s, operator—of the single-screen Colony Theater (now the six-screen Shaker Square Cinemas) on Shaker Square. In the mid-1980s, he also showed movies for a time at the Hanna Theatre in Playhouse Square (notably Claude Lanzmann’s nine-hour Shoah), outfitting that dormant legitimate theater with film equipment. In 1991 and 1992, he and Charles Zuchowski renovated and reopened the shuttered Heights Art Theatre/Coventry Cinema on Euclid Heights Boulevard as the Centrum. Morrie’s “empire” also extended to the Fairview twin cinema in Fairview Park (it closed in 1989), and he also managed the Tower City Cinemas for a time—when it was part of the Hoyts chain. (Hoyts, an Australian company, was the multiplex’s initial operator.) Beyond managing movie theaters, Morrie also worked for a while in film distribution and hosted a call-in, movie-oriented radio show on WHK AM 1420 in the early 1990s.

So Morrie held a lot of jobs during his long career. He also lost a lot of jobs. But he was resourceful enough (and famous enough) always to land on his feet. At heart, he was a salesmen, and the Zryl name and brand was one of his best commodities. Morrie was a promoter par excellence, and a shrewd showman from the old school. His stunts are legion and legendary. He regularly dressed up as characters in the movies he was showing (Napoleon, Mozart, the Tin Man, Tenderheart Carebear) to welcome patrons to his theater. He hired a helicopter to buzz around the city and blare the news that Apocalypse Now was opening at the Colony. He staged a chariot race around Shaker Square to promote a revival of Ben-Hur there. He served green popcorn at The Exorcist and dyed the snow around the Colony lilac for The Color Purple. In 1992, Charles Zuchowski, Morrie’s financial partner on the Centrum, projected that Zryl’s showmanship would save him $75,000 a year in advertising.

To Morrie, movies were meant to be seen on the big screen, in the best presentation possible, with all the attendant hoopla befitting a prestige production. This is how big-budget pictures opened and played at the downtown movie palaces during the 1950s and 1960s. Morrie sought to preserve and replicate that tradition during the 1980s at the Colony.

Opened in 1937 with a distinctive Art Moderne interior, the Colony was one of the grandest of Cleveland’s neighborhood theaters. It had a balcony, a huge marquee, and seated 1500. But by 1980, when multiplex theaters were popping up like mushrooms at local malls, having only one large screen was a liability. The Colony even closed in 1979. So when Morrie reopened it in 1981, he had to cover his overhead by nabbing the biggest and best first-run titles—for exclusive runs, if at all possible. When this proved impossible (the major film companies tended to favor those suburban, chain-owned multiplexes), he frequently fell back on 70mm revivals of films (like Star Wars) that did not originally open in that format in Cleveland. (Morrie always thought that Clevelanders deserved to see the biggest movies in the best presentation possible, and 70mm, six-track stereo was the gold standard at that time.) Similarly, if the city’s first-run theaters did not play an important foreign film or showed a film in the wrong aspect ratio (with heads or subtitles cut off), Morrie rectified the situation by booking the movie at the Colony. He always had area film buffs’ interests at heart.

Morrie’s loyalty to—and responsibility for—the Cleveland film market is something I can relate to. I also share his love for the grand, glorious movie theaters of yore. But time marches on and things change. Morrie’s unwillingness to split the Colony’s cavernous auditorium into smaller screening rooms is allegedly what caused him to lose his beloved showplace in 1991. (The next operator subdivided it.) But Morrie learned and he bent. His next venture saw him preserving (at least temporarily) another historic East Side movie house, the Heights Art/Coventry Cinema, by sub-dividing its single auditorium and balcony into three screening rooms, one with 70mm. But unlike the Colony, this conversion was done sensitively. None of the three screens shared the same wall, so there was no sound bleed-through from room to room.

Morrie left the Centrum less than year after the theater’s grand reopening in 1992, and Landmark took over the theater’s operation. I believe his next step was applying for the manager’s job at the Richmond Town Square Cinema 20 in Richmond Heights. I figured that Morrie, with his vast experience, was a shoo-in for the position. But the job went to somebody who had previously worked at Bob Evans. Apparently, food service experience was more important than film exhibition experience. Shortly thereafter, Morrie moved to Florida to continue his theater-managing career.

To Morrie, the movies were always the most important thing. The movies and the audience. He loved to hang out in the lobby and greet and mingle and talk movies with his customers. (He did this at the Colony, and he reportedly did this at the last theater he managed, the five-screen, second-run, ironically titled Last Picture Show in Tamarac, Florida.) Morrie was always the approachable public face of his cinemas—a warm, friendly, and funny character in an industry that has become increasingly anonymous and corporate. He will be missed in more ways than those who never met him ever will know.

-

Comments

0

- Tweet